CWS Market Review – September 8, 2021

(This is the free version of CWS Market Review. If you like what you see, then please sign up for the premium newsletter for $20 per month or $200 for the whole year.)

What Happened to Value?

A few days ago, the great tweeter Ramp Capital, asked, “What useless talent would you like to have that you can’t profit from?”

Nate Geraci answered, “Value investing.”

I have to admit I laughed.

It’s sadly true. Value investing hasn’t been a very good strategy for the last several years. In fact, value investing has lagged the overall market for more than 14 years. The last value peak came in May 2007.

How could this be? When I was getting my MBA, we were all taught that value investing was one of the strategies that could beat the market over the long term. There are gobs of academic studies to back this up.

The idea is simple enough: Load up on stocks with low P/E Ratios or high dividend yields, sit back, wait and eventually count your winnings. It makes sense. Value stocks were stocks that were tossed aside by the market for whatever reason, so value investors simply profited from stocks regressing to the mean.

But what’s happened since 2007? To be precise, value investing has been unprofitable. It’s merely been less profitable than growth investing. To be sure, there have been periods of value lagging before. But that’s usually been two to three years. Nothing like 14. The current growth cycle will soon be old enough to get her learner’s permit.

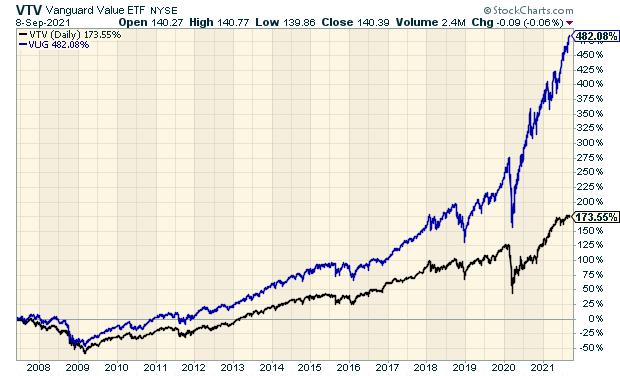

Here’s a chart of the Vanguard Value ETF (VTV), in black, along with the Vanguard Growth ETF (VUG), in blue, since May 2007.

Yikes! So what happened to value? The answer is interesting because it’s not really about value. Instead, it’s about how we measure value. This is what happens when you blindly follow one metric without looking at the broader picture. The value indexes are made based on a stock’s price-to-book ratio. By book value, we mean the accounting value of the company.

But this isn’t a neutral factor. Not by a long shot. The book values of many financial and energy stocks are very elevated. As a result, lots of stocks are being mislabeled, in my opinion, as being value stocks.

For example, nearly every major bank has a book value that’s fairly close to 1.0. Not many are above 1.6. Citigroup’s (C) is just 0.79. This means that nearly every major financial company gets put in the value bin. The same is true for many energy companies, but that’s not how it should work.

Ideally, the relative performance of the value index should reflect investors’ appetite for risk. Now it’s simply an index that’s heavily slanted to large oil companies and the major banks. Banks haven’t done that well since the financial crisis and the price of oil peaked in 2008. The value indexes aren’t telling us that value has been weak. Instead, they’re just reflecting the changes happening in two sectors of the economy.

Let’s look at some numbers. The S&P 500 Value Index currently has a 21.1% weighting in financial stocks and a 5.2% weighting in energy stocks. Meanwhile, financial stocks make up just 2.8% of the S&P 500 Growth Index. Energy stocks are a scant 0.1%. Banks and financials have nearly ten times the weighting in value that they do in growth.

This is an important lesson in stock analysis. Effect A may not be caused by Factor A. Instead, the inputs can be all wrong and as a result, you’re getting bad outputs.

If I had my way, the value and growth indexes would not be determined by the particular accounting of different industry sectors. Instead, I would base them on how each stock behaves. If a stock broadly moves with other value stocks, then it’s a value stock. Same for growth. The judgment of the market is smarter than that of accountants.

Free Onions!

It’s time to free onions. By that, I don’t mean cost-free onions. Instead, I mean we should liberate onions!

In the United States of America, it’s against the law to trade onion futures. In 1958, Congress passed the Onion Futures Act. This sounds like something made up by a satirical newspaper, but it’s all true.

How did this law come to be? Well, that’s an interesting story.

**Eddy lights his pipe**

It started back in 1955. That’s when two onion traders, Sam Siegel and Vincent Kosuga, cornered the market for onions. Think Goldfinger, but onions instead of gold.

It turns out that there are many layers to this story. It’s a dicey situation and it may end in tears. (Sorry.)

Onion trading was actually a big deal years ago. It was one of the most popular contracts on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. Siegel and Kosuga gradually bought millions of onions. They then shorted onion futures and dumped their vast onion horde on the market. The price for onions plunged. The price for a 50-pound bag of onions fell from $2.75 to just 20 cents. So many onions were going to Chicago that there were shortages in the rest of the country.

At one point, a 50-pound bag of onions was worth less than the bag that held them. As you might imagine, the public was not pleased. Siegel and Kosuga made millions. Meanwhile, farmers were crushed as they held vast amounts of worthless onions.

When the people get angry, that’s when politicians jump in. Congress passed the ban and President Eisenhower signed it into law. The bill was sponsored by Congressman Gerald Ford.

As a side note, the ban provided economists with a real-world arena to test an economic question: Does the presence of a futures market make the price of the underlying commodity more or less volatile? In other words, is speculation good or bad? Like many things economic, there’s conflicting data.

In recent years, onion prices have been very volatile. I think we’ll soon see onions futures return to the market.

(Yesterday, someone on Reddit wondered if their grocer’s coupon for onions violated the law. It doesn’t.)

Stock Focus: Reynolds Consumer Products

This week’s featured stock is Reynolds Consumer Products (REYN). I have to confess that I love consumer products companies.

I say this for several reasons.

The first is that these are often products consumers pretty much have to buy. Reynolds for example, makes Reynolds Wrap. Everyone has heard of it and nearly everyone uses it.

This is important because when the economy goes into a nose-dive, folks generally don’t cut back much on their household items. Instead, you’ll see broad weakness in areas like vacation-oriented businesses or homebuilders.

When the economy is on its knees, people cut back on the expensive stuff. Sales of Reynolds Wrap, not so much.

This is also important because we’ll witness steadier business performance. When looking at the financial statements of a consumer products company, we’ll probably see steady increases in sales, profits and dividends. This makes forecasting much easier, and that makes it easier for us to value a stock.

As a stock-picker, I’m always leery of companies that rely too much on “the promise” of future growth. With these defensive companies, there’s less guesswork.

Found in Nearly Every American Kitchen

First, let’s look at the back story of Reynolds Consumer Products. Reynolds’s products can be found in 95% of American kitchens. Open one drawer and you’ll see Reynolds Wrap and Reynolds Aluminum Foil. Look under the sink and there are the Hefty Bags. Look somewhere else and you’ll see paper plates and cups. Reynolds makes the stuff you usually don’t think about but would certainly miss if it wasn’t around.

Reynolds also does a nice business with “private labels.” In plainer terms, this means Reynolds also makes the store-brand knock-off stuff you see in the shopping aisles. The private label business usually does better during a recession, but Reynolds does well since they have both ends of the market covered.

Reynolds is also the exclusive private label supplier to Amazon.

Reynolds usually ranks #1 or #2 in just about every product segment. Most shoppers know the names and that helps brand loyalty. The company generates $3.2 billion in sales annually.

Who doesn’t love a red solo cup?

The company used to be part of Alcoa, but they were sold off to a private equity firm a few years ago. Reynolds then had its IPO in January of last year. This was before the coronavirus hit the U.S. economy and stock market.

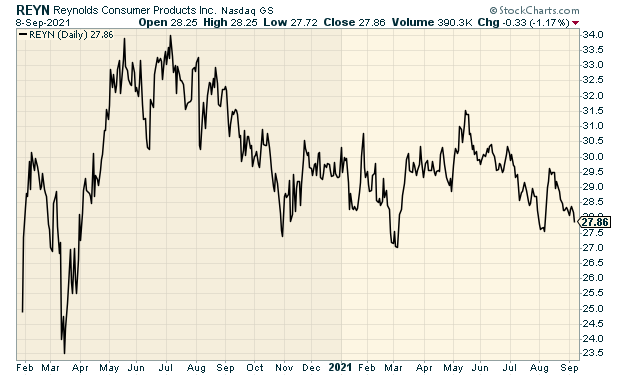

The IPO was priced at $26 per share, and investors liked what they saw. On the first day of trading, the shares got as high as $29.46. Within a few days, they were on the doorstep of $32 per share. The rally soon ended as the economy went into lockdown and the shares plunged below $22.

That’s actually not so bad when you compare it to everyone else. When people get scared, they seek out quality.

Pretty soon, Reynolds made back everything it lost and by early June, the stock made an all-time intra-day high of $36 per share. Since then, the stock has slowly drifted lower. When a good stock lags like this, it gets my attention.

Reynolds has already increased prices twice this year without any major problems. That’s a very good sign. In previous issues, I’ve talked about how the ability to raise prices is a good sign of having a competitive edge.

I also like that the company generates a lot of cash flow. One of my concerns is that the company carries a lot of debt. (That’s often a shady IPO strategy. The mother company shoves its debt onto the company they’re about to spin off.) While Reynolds does have a lot of debt, it can be managed; but it will take time and, of course, money. In fact, the company has already pared back its debt position.

Last month, Reynolds reported fiscal Q2 earnings of 39 cents per share on sales of $873 million. That topped estimates by one penny per share. Reynolds expects full-year earnings between $1.54 and $1.64 per share. That’s probably too low but only by a few cents per share. Reynolds pays a quarterly dividend of 23 cents per share. That works out to a yield of 3.30%.

There’s a lot I like about Reynolds Consumer Products. If the Q3 earnings report is good, REYN could be a member of our 2022 Buy List.

I’ll have more for you in the next issue of CWS Market Review.

– Eddy

P.S. If you haven’t had a chance, you can subscribe to our premium newsletter. It’s only $20 a month or $200 a year. Please join us!